Recommendation: Short (No Change)

€--

$70m

FY’20 Price/FCF

€--

€11.7bn

20x consensus

-70%

WDI GY

15x The Analyst adjusted

Investment Thesis

Wirecard always reports stellar EBITDA growth and the market rates the stock on ~40x PE as a result. We see consistently poor cash generation and rising debt levels as indicative of rising capital intensity and weaker returns than the market believes.

New allegations have emerged from reputable journalists that lead us to question the accounting, particularly in relation to large M&A deals.

The company’s responses raise more concerns rather than providing comprehensive and compelling information to discredit the authors at SIRF and the Financial Times. Investors are essentially being asked to believe that an unknown private-equity firm made 800% in five weeks by flipping a small Indian asset to Wirecard in late 2015.

In this note, we continue our conversation from the 2017 notes that discussed the low return on equity of the business, the capital-intensity of the growth, and the changes in accounting disclosures.

For deeper background reading, please refer to our two previous notes and our video from our Shorts conference:

- The Death of Fundamental Accounting Shorts or Peak Euphoria? (October 2017)

- Opaque Structure Hides €180m (November 2017)

- Shorts Conference Recap (November 2017)

The Wirecard debate has heated up again in 2018, with two notable articles posted at SIRF and the Financial Times about an Indian acquisition. This matters, because the acquisition of the Indian assets cost more than 100% of Wirecard’s 2016 profit and over two years’ free cash flow. We have received some concerning comments and saw one broker state the following:

‘Indian entity’s €340m price tag translates to c. 3% of Wirecard’s total EV. i.e. even if the operations were as bad and shady as indicated by the usual suspects, exposure to this asset is limited.’ (Source: Unnamed to protect the author)

We think this misses the point somewhat. The acquisitions followed a complex, confusing, and unusual pattern, typical of other Wirecard deals in Asia. For an outsider to comprehensively track cash flows relating to M&A is extremely difficult – if not impossible – which is why investors must place a high level of faith in the Wirecard management and treat investigative articles with adequate consideration. After a nine-year bull market and a fantastic share price performance, the incumbent sell-side is completely unquestioning and consensual on the matter. Even if these claims prove to be completely unfounded, the debate must be conducted, as the suggestions are extremely severe.

We look forward to further information from the company, and would like more comprehensive responses with greater detail to ascertain the veracity of the journalists’ claims and understand why they are wrong. These are serious claims and the burden of proof should be accordingly high. We welcome the increased scrutiny of large, German-listed companies, in the wake of the Steinhoff scandal. However, we remain cognisant of the vested interests of hedge funds with short positions and the possibilities of market manipulation. We would like additional information from BaFin regarding the extent of its investigations, the grounds on which it is investigating various authors, and to what extent it is engaging with the information in a collaborative manner. We watch with interest and remain short on Wirecard for fundamental reasons, as outlined in previous research notes.

Wirecard’s responses to SIRF are, on balance, concerning.

Wirecard’s various responses were provided to market participants indirectly through the sell-side brokerage community and are not yet conclusive. We still have not seen a public statement issued on Wirecard’s investor relations website at the time of publishing this report, and we would like to see some discussion of these issues on the next public conference call. Unfortunately, the attitude of the analyst community is to disregard any negative criticism of the company. Responses were provided to SIRF and these have been published. Our concerns are specifically:

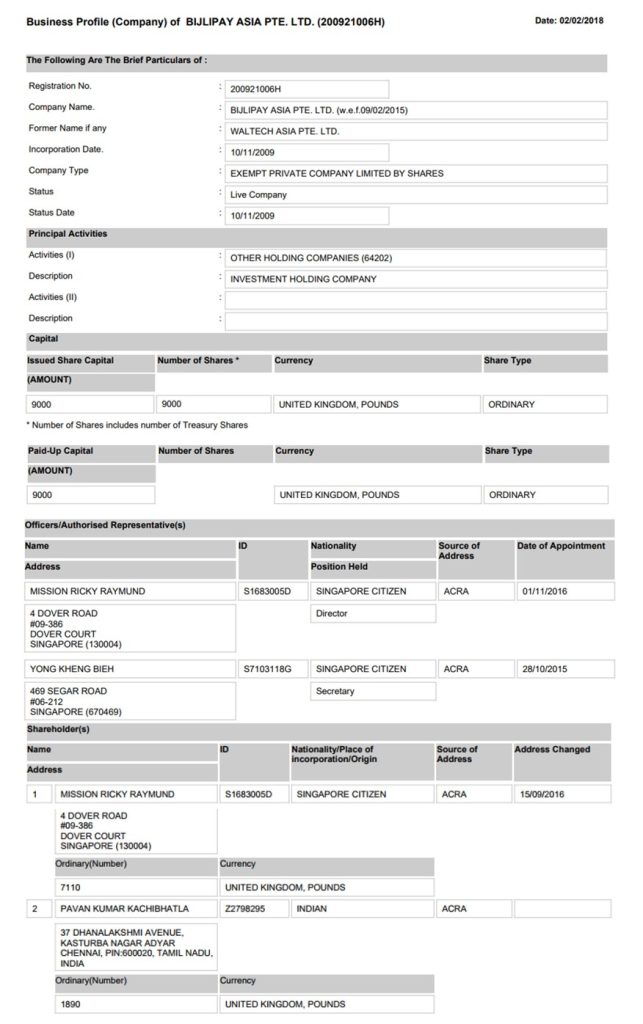

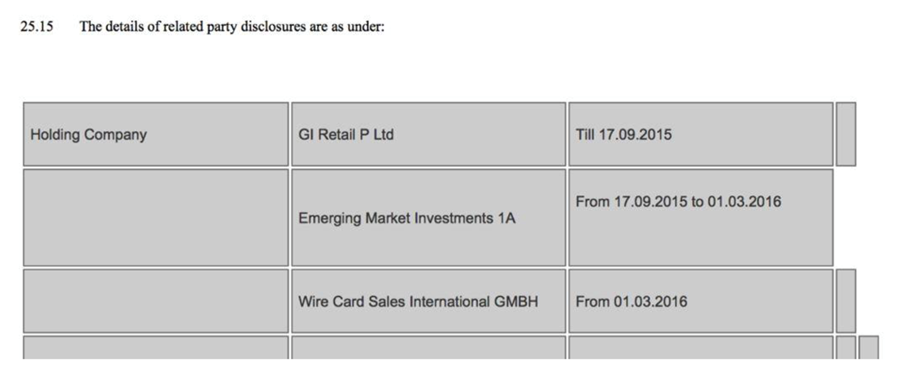

1. What Is Emerging Markets Investment Fund 1A/Emerging India?

The company seems to confirm it bought the Indian assets directly off Emerging Market Investment Fund 1A (EMIF1A), a fund in Mauritius controlled by Emerging India and incorporated by the Trident Trust.

Exhibit 1: The Fund and Private Equity Vehicle that Sold to Wirecard

Source: CBRD and Emerging India Fund Management

Accordingly, Wirecard’s claim now is that the cash went into a Mauritius entity (which likely explains why the smaller amount of €40m shows in Indian FDI filings). Hermes was the main asset with economic value, and this was deconsolidated from the GI Retail accounts upon transfer to EMIF1A (in late September 2015), not on transfer to Wirecard (which explains why the smaller profit on sale of €40m appears in the GI Retail accounts).

The assets of Hermes, GI Technology, GI Philippines, and Star Global were acquired from EMIF1A just a few weeks after EMIF1A acquired them from the founders and shareholders of GI Retail. This leaves several questions outstanding.

- Who are the beneficiaries of EMIF1A and why was this never publicly mentioned before by Wirecard, at the time of acquisition, nor in the 2016 annual report? In other acquisitions, Wirecard mentioned private equity vendors. Specifically, Provus Group (a Romanian acquisition of €32m) was sold by a Polish private equity fund Innova Capital and Moip (a Brazilian acquisition of €24m) was sold by a Brazilian private equity fund Ideiasnet S.A.

- How could a previously relatively unknown private equity fund, of a largely unknown private equity parent (Emerging India), make 8x its money in just five weeks, between acquiring assets from GI Retail and then selling them to Wirecard? The response and explanation suggests that EMIF1A became the holding company of Hermes on 17 September 2015, before selling it to Wirecard for €340m on 27 October 2015. This is simply an incredible >800% return in 40 days. We acknowledge that strange things happen in equity capital markets, but we find this ridiculous.

Exhibit 2: Hermes Transferred to EMIF1A 17 Sept 2015, Wirecard Announced Acquisition 27 Oct 2015

Source: Hermes I Tickets Accounts 2016

- Aside from the absurdity of this situation, and the questions Wirecard shareholders should ask about capital discipline, the other possibility is that EMIF1A bundled other assets into the deal. However, we know Hermes was the substantial asset in the group, and most of the goodwill was attributed to this business, whilst GI Philippines was a subsidiary of Hermes and GI Technology was only bought for €15m (€1m and a subsequent €14m capital raise). Star Global was a tiny business and would not explain the balance of payments.

- If Wirecard had an established relationship with Hermes, dating from before the M&A transaction, why did it miss the opportunity to acquire it in 2014 (when it was first marketed for sale)? Why didn’t, or why couldn’t Wirecard buy it before EMIF1A bought it? Why did it let Emerging India make €300m on the deal?

- Why are minority shareholders in Hermes bringing legal action against the vendors in the UK? The Financial Times reports that a commercial lawsuit was filed in the UK high court in October 2017, by minority shareholders in Hermes. The paper alleges that ‘they were told the Mauritius entity ‘had made an offer to purchase Hermes for approximately $40m’ and that the ultimate sale to Wirecard had been concealed from them’ (Source: Financial Times). Importantly, and fortunately for Wirecard shareholders, Wirecard is not named as a defendant. However, Ramu Ramasamy, who is a Managing Director of Wirecard in India, is named. Ramasamy has been presented at Wirecard investor events, and we look forward to watching developments with this legal action.

- Why does Wirecard suggest there were other large shareholders in Hermes, other than GI Retail, when there were not? It has come to our attention that some sell-side analysts reported that according to Wirecard there was an additional founder/big shareholder and that the missing €176m was paid to a party outside GI Retail. We would like to know who this mystery person/founder/shareholder is as we were unaware of other shareholders from the Hermes accounts. We understand the Ramasamy brothers (Ramu Annamalai and Palaniyapan) were the primary shareholders through GI Retail.

Is Wirecard a Scalable Payment Processing Platform or a Bank – or Both?

We have identified an example of a FinTech receivable here. Aside from the corporate governance concerns it raises, it allows us to develop our understanding of Wirecard’s cash flow statement further. In the detailed section below, we look at the interlinked companies; Wirecard, Senjo Group, Skilworth, Bijlipay, Orbit and Goomo. This matters for investors because it shows that Wirecard sends money to its customers in the form of a loan, and without those loans the growth rate of the company may be materially lower. Furthermore, it demonstrates that Wirecard often operate through a web of related-parties, and this may increase the risk profile of the earnings, or the sustainability of growth.

Previously, growth in FinTech receivables were obscure accounting items in Wirecard’s accounts (excluded from the adjusted cash flow statement). Now we have a live example of the money flow. Essentially, Wirecard spends significant amounts of capital to grow – more than a normal payment processor, as it extends loans to business partners. We do not know the duration, risk profile, or lending rate on these loans. However, this aspect of Wirecard should certainly be valued more as a banking business rather than scalable processing/technology business. We do not see any wrongdoing in this method of business, as the company is simply using the deposits available via its banking business to fund its supply chain. However, it does increase the risk profile and change the nature of the equity investment for shareholders – many of whom believe Wirecard is simply a scalable technology platform processing increasing volumes through the payment engine.

The price/book multiple that investors attribute to the stock and the earnings multiple of ~40x looks increasingly incongruous in light of this analysis, as very few banks trade on these multiples.

2. Senjō Group Singapore & Fintech Receivables

An interesting business partner of Wirecard has been introduced into the debate through questions asked by SIRF, and in Wirecard’s subsequent responses.

Exhibit 3: Wirecard and Senjō Relationship Comes to Light via SIRF

Source: Wirecard, through Its Response to SIRF through Elliot Sloane of FTI Consulting

We now discuss the Senjō Group and Wirecard’s ‘partnership in place’ with Bijlipay India in the context of our attempts to understand the complexity of Wirecard’s business model, aside from the simple, scalable, payment processing engine. Wirecard states that ‘Senjō is a fintech company headquartered in Singapore with operations around the world. It is a business partner of Wirecard.’ Senjō provide more details on its website.

- In what respect is Senjō a ‘business partner of Wirecard’? As Senjō is ‘a new type of global payments operator and FinTech investor’ it appears to have the same model and exposure as Wirecard. In fact, the business looks very similar to Wirecard, but we do not know whether Wirecard processes payments or provides additional support services to Senjō. Do the two partner on acquiring payment volumes, does Wirecard pay Senjō, or does Senjō pay Wirecard as a customer?

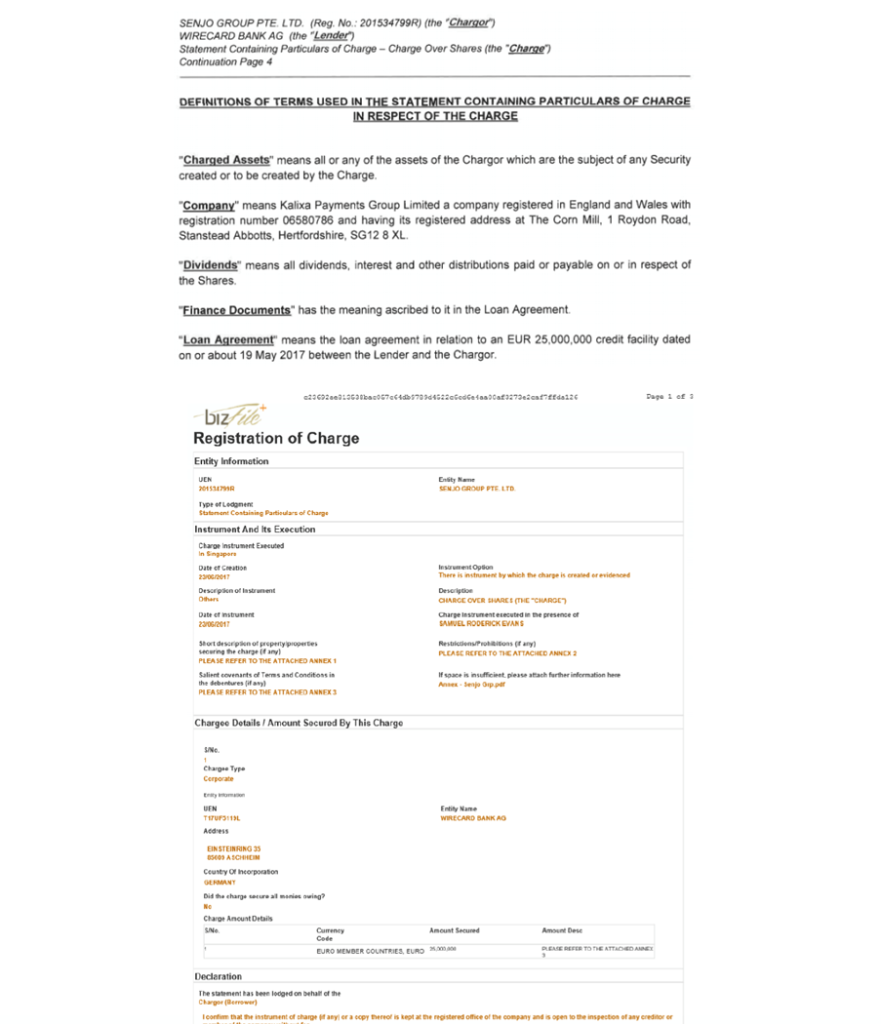

- Wirecard has provided a loan of €25m to Senjō Group. We assume this is an example of a FinTech receivable (as detailed in the company’s cash flow statements). If Senjō is a customer of Wirecard, and Wirecard is providing a loan to that customer, it raises a concern about the quality of the revenue and growth as well as the capital-intensity of the business model.

- At 9M’17, Wirecard disclosed €127m of ‘Financial and Other Assets: Receivables from bank business (mostly from FinTech business) and €105m ‘Trade Receivables: Receivables from bank business (mostly from FinTech business).

- The increase in FinTech receivables is excluded from Wirecard’s adjusted cash flow statement, yet we can see in the Senjō case that Wirecard is clearly lending money to its business partners.

- Growth in FinTech receivables should not be excluded from any analysis of Wirecard’s cash flows and is consistent with the increasing capital-intensity thesis on the stock – that money leaves the company to fuel the growth and that is why cash generation is materially below the company’s chosen accounting metrics, whilst significant capital spend is required to fuel growth.

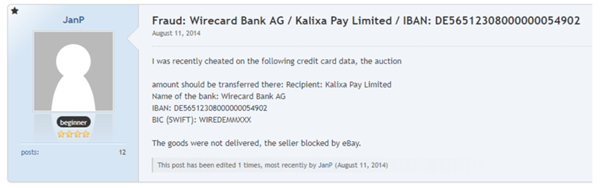

It appears that Senjō Group may have used the Wirecard loan to acquire Kalixa payments from GVC Holdings PLC. It appears that Kalixa used to use Wirecard Bank AG as a bank accounts for its deposits.

Is Senjō, or its operational subsidiary Bijlipay, or a company called Qtail, customers of Wirecard? Why does this matter?

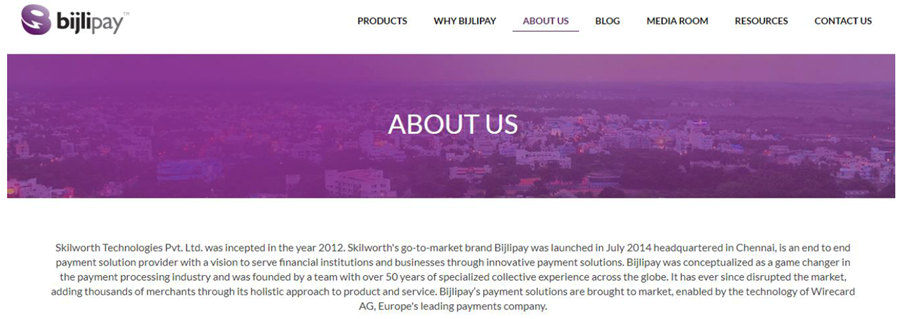

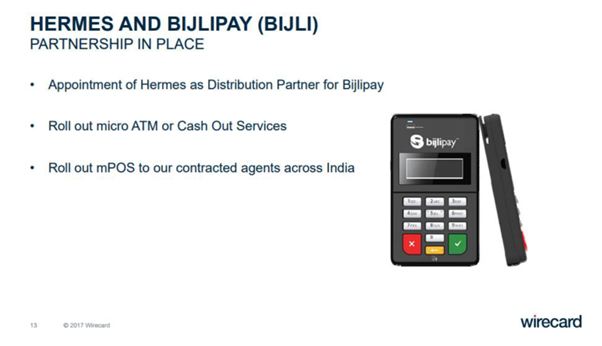

Bijlipay was described at Wirecard’s Indian Investor Day in 2017 as a partnership in place since 2014 with Hermes. Bijlipay appears to be driving much of the growth in India.

Exhibit 7: Hermes (Wirecard) and Bijlipay Are Partners in India

Source: Wirecard Investor Presentation 2017

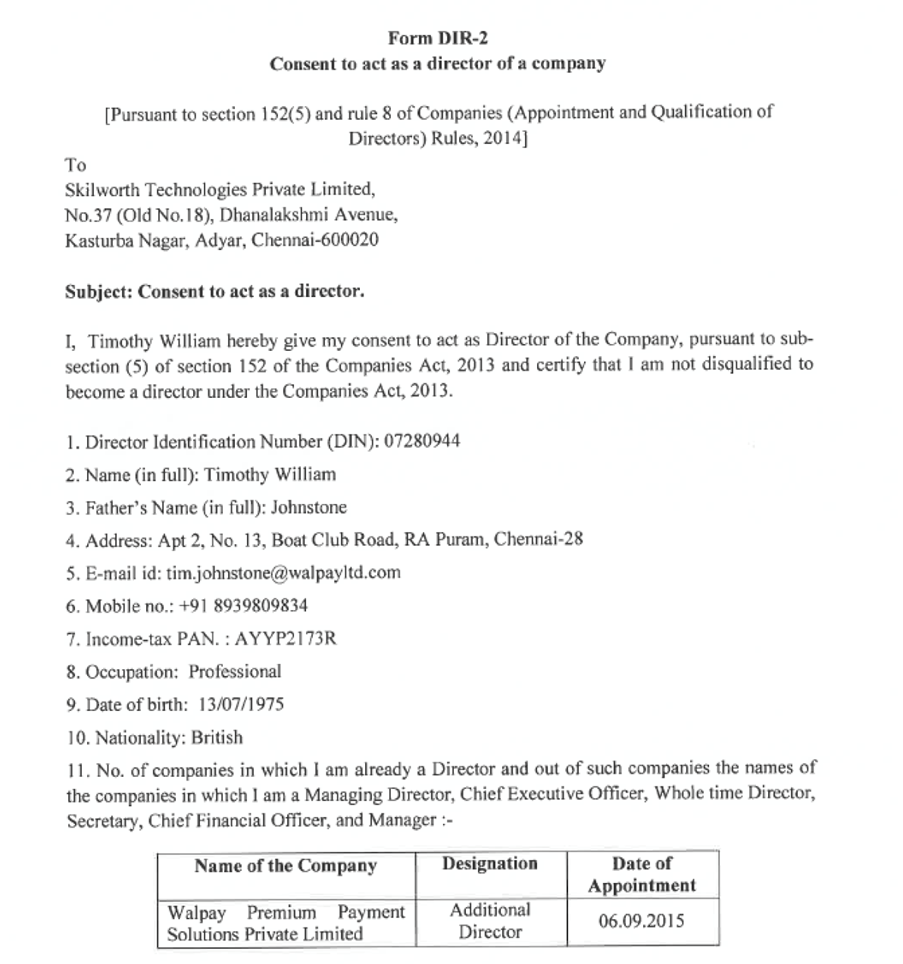

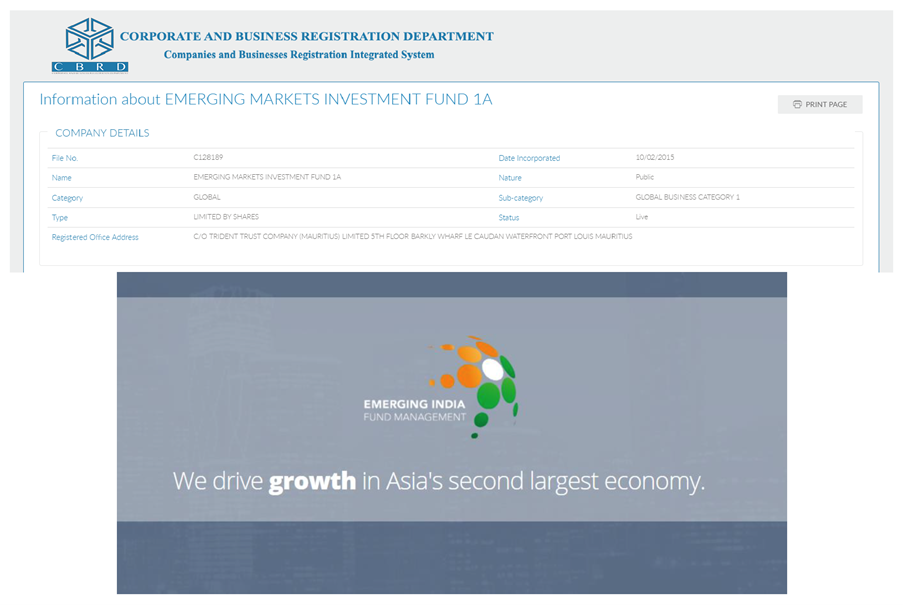

Bijlipay is owned by, and is the trademark of, a company called Skilworth Technologies Private Limited.

Skilworth is owned by Bijlipay Asia Pte Ltd, which is owned by Pavan Kumar Kachibhatala and Ricky Raymund Mission.

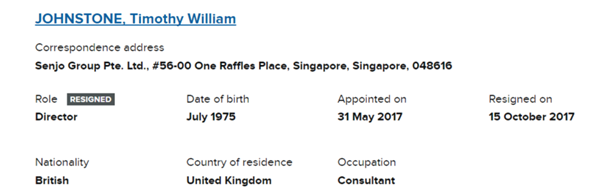

Skilworth has another director Timothy William Johnstone, who is head of Senjo Payments, which is part of Senjo Group.

Exhibit 11: Timothy Johnstone was also a director of Senjo Group

Source: UK Companies House

Bijlipay’s CEO, Pradeep Oommen, is also a director of another Indian company called Qtail (despite declaring he is not a director in any other company in Skilworth’s reports).

Exhibit 13: Bijlipay’s CEO is a director of Qtail

Source: Qtail India Private Limited FY’16 Annual Report

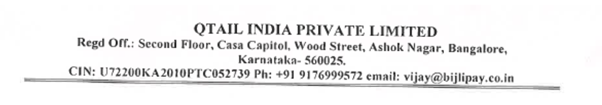

Qtail India Private Limited shares operations with Bijlipay, as we can see from the correspondence address and the email address in the header of Qtail’s FY’16 Annual Report.

Exhibit 14: Qtail’s Address in India

Source: Qtail India Private Limited FY’16 Annual Report

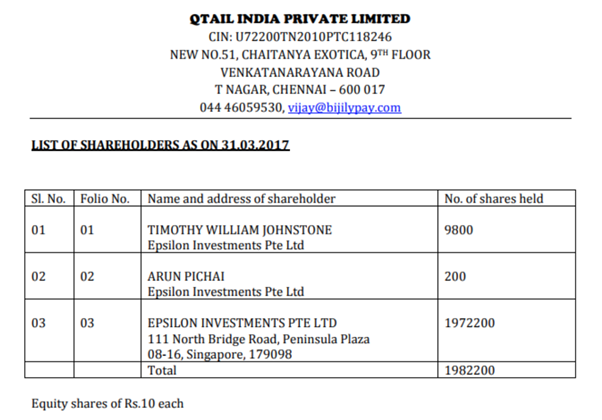

Qtail India Private Limited is 1% owned by Timothy William Johnstone, and 99% owned by Epsilon Investments Pte Ltd. Timothy William Johnstone is also a director in the company.

Exhibit 15: Qtail shares an address with Bijlipay

Source: Qtail India Private Limited List of Shareholders

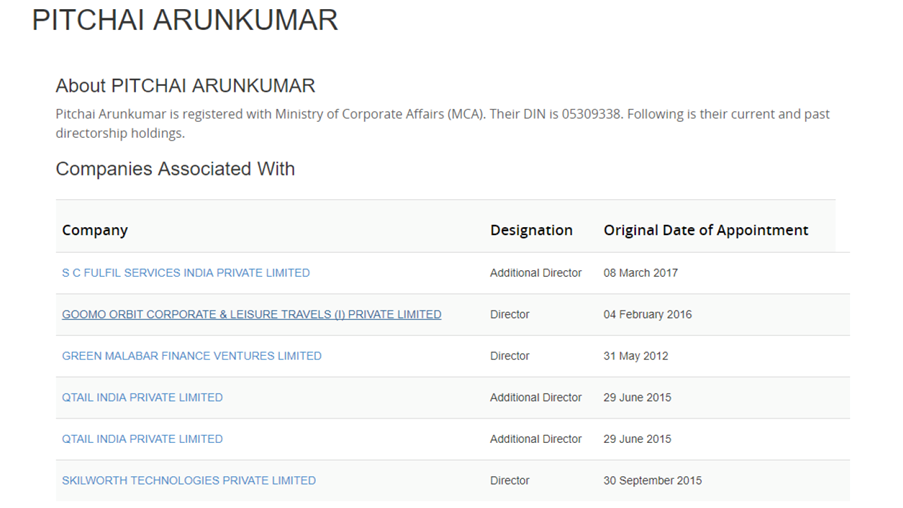

The third director in Qtail is Pitchai Arunkumar, who is also a director in Skilworth Technologies Private Limited, S C Fulfil Services India Private Limited, Green Malabar Finance Ventures Limited, and Goomo Orbit Corporate & Leisure Travels (I) Private Limited.

Goomo Orbit Corporate & Leisure Travels (I) Private Limited is owned by Goomo Holdings Services India Private Limited, whose directors are Rajan Puri, Vasudevan Raghavan and Varun Gupta.

Rajan Puri is also a director in Orbit Corporate & Leisure Travels (I) Private Limited, which in turns got several rounds of investments from EMIF1A. The link between Wirecard and Orbit has been largely explained by SIRF.

Senjo Group also owns a software consultancy business called Qtail Pte Ltd, whose main area of expertise is eCommerce. Qtail Pte Ltd in turns owns Qtail Limited in the UK. In the filings, we find that Keith James Wooodhead is a director. This person is linked to several ePayments companies operating in high-risk countries, and one of his correspondence addresses is 2nd Floor, 12 Tower House, Castle Street, Douglas, Isle of Man. This is the same address of Walpay Ltd. Qtail India’s old name was Walpay Premium Payment Solutions Private Limited.

These links suggest Wirecard, Senjō, Bijlipay, Goomo, Orbit and Qtail are related parties, or at least share some addresses and directors. Yet, Wirecard funds Senjō through its bank. We are concerned by this web of interconnections, specifically because money flows from Wirecard bank into customers and partners, and if any of these companies are customers of Wirecard, then Wirecard is funding their customers and their own revenue.

- Did Senjō use the loan from Wirecard to acquire Kalixa from GVC? Is Kalixa a customer of Wirecard?

- What is the nature of the relationship between Wirecard and Senjō, described by the company as a ‘business partner’, but in fact, the recipient of a large loan, and engaged with other businesses such as Bijlipay, Orbit, Goomo and Qtail, which are other partners of Wirecard? What are the terms of the loan to Senjō, and what other companies are beneficiaries of funding from Wirecard through the use of balance sheet to grow FinTech Receivables? Is it possible for the loan to return to the company as revenue?

Conclusion

We maintain our Short recommendation and €30 price target.